Because these are vintage rides, they're restricted to road-racing bikes (or at least road-racing type bikes; the rules seem to leave a little wiggle room here) manufactured before 1987. No clipless pedals are permitted, and all bikes must have exposed, non-aero brake cables and down-tube shifters. Wool jerseys, shorts, and similar period dress is encouraged. Riders can choose from three courses ranging from 40 miles or so to a bit more than 120 miles. All include an abundance of hills and significant stretches of gravel road.

The whole thing sounds like a lot of fun to me, and I'd love to ride in one someday. So far, though, my participation has been limited to selling chainrings to riders who are going, and providing some suggestions on modifying their gearing. Here are a few gearing recipes that should work well for those who want lower ratios for an Eroica ride:

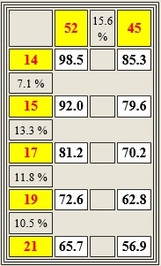

Chart 1. This brutal set of ratios is the actual catalog spec for the 1974 Peugeot PX-10. That's a 57-inch low gear! That was too high for even the younger version of me, and it's way too high for the current one.

Chart 1. This brutal set of ratios is the actual catalog spec for the 1974 Peugeot PX-10. That's a 57-inch low gear! That was too high for even the younger version of me, and it's way too high for the current one. 122 BCD Doubles with French Derailleurs

If your vintage ride is a 1960s or 70s French-made road racing machine, there's a good chance that it came equipped with a Stronglight Model 63, 49D, or 93 crankset, all of which accept 122 BCD chainrings.

Rings as small as 37 teeth are possible in that size, although the smallest that Stronglight officially made was a 38-tooth version. But many, if not most Stronglight doubles of that era left the factory with 52-45 rings. When coupled with the typical narrow-range freewheel the resulting gearing is heroic indeed (see Chart 1). The 57-inch high is just too tall a gear to carry most non-racing cyclists over long climbs without a lot of suffering, and probably some walking.

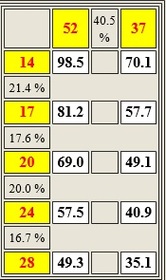

Chart 2. To get seven unique, evenly-spaced gear combinations from this setup, stay on the big chainring through the first three or four freewheel cogs, then double shift by dropping to the small ring in front and shifting to the 17- or 20-tooth cog in back.

Chart 2. To get seven unique, evenly-spaced gear combinations from this setup, stay on the big chainring through the first three or four freewheel cogs, then double shift by dropping to the small ring in front and shifting to the 17- or 20-tooth cog in back. The resulting gearing, charted at left, is much more humane. The Simplex "Prestige" rear derailleurs supplied with most French (and many non-French) bikes of this era have the capacity to handle this setup with ease, provided that the chain is no longer than necessary to handle the 52-28 combination.

It's a good thing, too, because changing rear derailleurs on an older French bike can get complicated. (For more on this, see the earlier blog post "Derailleur Hangers Demystified.)

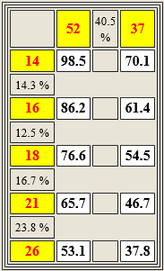

Chart 3. The tighter freewheel called for by a Campagnolo Record derailleur yields even spacing between gears, but slightly higher ratios compared to the setup in Chart 2, above.

Chart 3. The tighter freewheel called for by a Campagnolo Record derailleur yields even spacing between gears, but slightly higher ratios compared to the setup in Chart 2, above. For bikes with 122 BCD cranksets and Campagnolo Record derailleurs,the situation is slightly different. The crankset will accept a replacement 37-tooth inner ring in front, but the 28-tooth freewheel cog may be a bridge too far for the rear derailleur. Some Campagnolo Records will shift onto a cog of that size with ease, while others will clatter madly and fail to get over the hump.

The ability—or inability—of a Record derailleur to handle a 28-tooth cog depends the length of the derailleur hanger and perhaps other factors. The best way to determine whether the combination will work on a given bike to bolt it on and give it a try. If it does make the shift, be aware that the combination of a 14-28 freewheel and 52-37 front exceeds the total capacity of the Campy Record rear by several teeth, meaning that the chain will hang a bit slack in the small-to-small 37-14 combination. But provided you stay out of that gear (as you should anyway, since it forces the chain to run at an extreme diagonal) you should be fine.

If a 28-tooth doesn't work with your setup, a 14-26 freewheel almost certainly will, although--as you can see from Chart 3--that will take a couple of gear-inches off your low.

Another choice is to replace the original Campagnolo Record cage with an aftermarket long cage from Soma Fabrications, which will reportedly handle freewheel cogs of up to 32 teeth. (You can find more information on Soma cages here. I haven't yet had a chance to try one myself, but I've heard good things about them.)

144 BCD Campagnolo Doubles

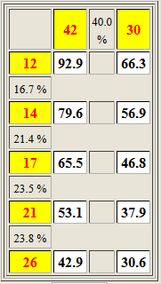

The 144mm bolt circle diameter Campagnolo used for its Record and Nuovo Record cranks from 1967 until well 1985 or so limits the user to cranks of 41 teeth or larger. Practically speaking, that means 42 teeth, since 41-tooth rings are scarce, costly, and in any case pretty much indistinguishable from 42s when climbing a hill.

Combining a 42-tooth small ring with a 26-tooth freewheel cog (which, as we’ve seen is the largest that a stock Campagnolo Record derailleur will reliably handle) gives you a low gear of about 43 gear inches. If you’re determined to keep the Campagnolo double crank, the only way you can go lower is by switching to a higher-capacity derailleur (or the Soma aftermarket cage mentioned above) and a wider-range freewheel.

If you can live with a 93-inch high gear (like the preceding charts, this one assumes 700 wheels and tubular tires; with beefier clinchers all the ratios will be a bit higher), you can put together a home-brewed compact double with a triplizer ring and the 74 bcd inner ring of your choice.

If you can live with a 93-inch high gear (like the preceding charts, this one assumes 700 wheels and tubular tires; with beefier clinchers all the ratios will be a bit higher), you can put together a home-brewed compact double with a triplizer ring and the 74 bcd inner ring of your choice. Unless, that is, you’re the mechanically adventurous type, and want to assemble what could be described as a “triplized double:” This involves installing a triple bottom bracket spindle and mounting a triplizer ring and attached granny ring in the inner position, with a toothless “bash guard” in place of the usual outer ring. I’ve done this with a Stronglight 93 crankset—it’s described in detail in the blog post “Installing a Triplizer as a Compact Double”—and there’s no reason it shouldn’t also work with a Campagnolo crank.

But really, if you’re going to install a spindle suitable for a triple crank—as the Chart 4 setup requires—it probably makes more sense to install a third chainring in place of the bash guard and get the even wider gearing range.

I’ll discuss some Eroica-appropriate triple setups in my next post.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed