Golly! It sure is nice here in Tuscany!

Golly! It sure is nice here in Tuscany! Are you going to need a triple to ride the Eroica? Hey, don't ask me. Maybe you’re younger and tougher—or just tougher—than I am. But there are a lot of hills and some dirt road. I’d need one if I were riding it.

A triple crank has two small advantages over a double, and one big one. It gives you a few more gear combinations, which is kind of nice, and the jumps between gears are also a little smaller. That’s also kind of nice. But the big reason people switch to a triple is that it gives you at least a couple of gears that are substantially lower than what you could hope to get out of a standard double.

Of course, there’s also a significant disadvantage to a triple, in that shifting is a little fussier. Feeling your way between three front chainrings takes a lighter touch and more practice than just throwing the front-shift lever all the way in one direction or the other, as you can with a double.

Long-Cage vs. Short-Cage Derailleurs

I’m often asked whether converting a double crank to a triple also requires a switch from a short-cage to a long-cage derailleur.

The answer—you knew this was coming—is “it depends.”

Rear derailleurs have two key attributes. The first has to do with the largest freewheel cog they will accept. Many short-cage derailleurs of the 60s and 70s can handle a 28-tooth cog, although some—like the Campagnolo Record or Nuovo Record—top out at 26 teeth.

A triple crank has two small advantages over a double, and one big one. It gives you a few more gear combinations, which is kind of nice, and the jumps between gears are also a little smaller. That’s also kind of nice. But the big reason people switch to a triple is that it gives you at least a couple of gears that are substantially lower than what you could hope to get out of a standard double.

Of course, there’s also a significant disadvantage to a triple, in that shifting is a little fussier. Feeling your way between three front chainrings takes a lighter touch and more practice than just throwing the front-shift lever all the way in one direction or the other, as you can with a double.

Long-Cage vs. Short-Cage Derailleurs

I’m often asked whether converting a double crank to a triple also requires a switch from a short-cage to a long-cage derailleur.

The answer—you knew this was coming—is “it depends.”

Rear derailleurs have two key attributes. The first has to do with the largest freewheel cog they will accept. Many short-cage derailleurs of the 60s and 70s can handle a 28-tooth cog, although some—like the Campagnolo Record or Nuovo Record—top out at 26 teeth.

The Campagnolo Rally derailleur was basically a Record model with different graphics and a long cage. Most Campy Records will accept an aftermarket cage patterned after the one on the Rally.

The Campagnolo Rally derailleur was basically a Record model with different graphics and a long cage. Most Campy Records will accept an aftermarket cage patterned after the one on the Rally. The second is something called "total capacity," which measures the ability of the spring-loaded derailleur cage to keep the chain acceptably tight as it moves between cogs of different sizes during shifting.

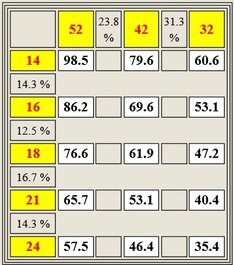

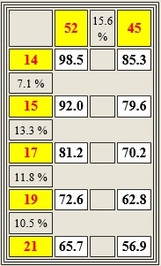

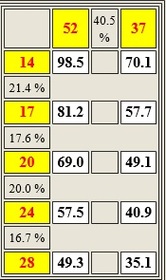

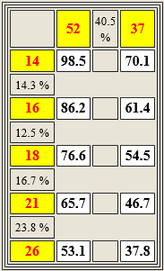

The capacity of a given gearing setup is simply the total difference between the tooth counts of the largest and smallest chainrings and freewheel cogs. For example, the difference between the largest and smallest rings of a 52-42-28 triple is 52 minus 28, or 24. The equivalent figure for a 14-28 freewheel is 24 minus 14, or 10. Add the two figures together and you get a total of 34.

If your derailleur has a total capacity of that much or more (judicious use of google should help you find up the manufacturer’s rated capacity of any rear derailleur you’re thinking of using), you’re home free. Provided that your chain is no longer than it needs to be to handle the 52-28 combination of big chainring and big freewheel cog (more on this a little later), it will have enough “takeup” to keep the chain from going slack even in the 28-28 small-to-small combo.

Generally speaking, derailleurs with capacities of 32 to 40 or more teeth are considered to be long-cage, and those with capacities of 26 teeth or fewer to be short-cage. A smaller mid-cage category includes those with capacities of 30 to 32 teeth.

The capacity of a given gearing setup is simply the total difference between the tooth counts of the largest and smallest chainrings and freewheel cogs. For example, the difference between the largest and smallest rings of a 52-42-28 triple is 52 minus 28, or 24. The equivalent figure for a 14-28 freewheel is 24 minus 14, or 10. Add the two figures together and you get a total of 34.

If your derailleur has a total capacity of that much or more (judicious use of google should help you find up the manufacturer’s rated capacity of any rear derailleur you’re thinking of using), you’re home free. Provided that your chain is no longer than it needs to be to handle the 52-28 combination of big chainring and big freewheel cog (more on this a little later), it will have enough “takeup” to keep the chain from going slack even in the 28-28 small-to-small combo.

Generally speaking, derailleurs with capacities of 32 to 40 or more teeth are considered to be long-cage, and those with capacities of 26 teeth or fewer to be short-cage. A smaller mid-cage category includes those with capacities of 30 to 32 teeth.

The "B" adjustment screw is visible just to the right of the derailleur mounting bolt in this back view of the venerable and much-loved Suntour VGT Luxe

The "B" adjustment screw is visible just to the right of the derailleur mounting bolt in this back view of the venerable and much-loved Suntour VGT Luxe "Cheating" on Derailleur Capacity--How and How Not To

But manufacturer-specified capacity figures tend to be pretty conservative. (Their "largest cog" specifications, on the other hand, are usually just about right.) Most derailleurs will take up a bit more slack—typically a tooth or two more—than the spec sheet says they will. You can often pick up another tooth or two by tightening the derailleur’s “B” adjustment screw as far as it will go, so the body of the derailleur is rotated as far back as possible.

The official capacity figure also assumes that the derailleur needs to keep the chain taut at all times, even when it’s parked on granny chainring in front and the smallest freewheel cog in back.

But because we’re experienced cyclists, you and I would never use that combination anyway, since we know that it puts the chain at an extreme angle and causes rapid drive-train wear.

Come to think of it, we would never use the granny ring with either of the two smallest freewheel cogs, given that better-aligned approximations of the same ratios are usually found on the middle chainring.

And if you’re willing to make a firm policy of staying out of the smallest cogs in combination with the small chainring, your derailleur effectively gains a few additional teeth of capacity--enough, perhaps, to allow your short-cage derailleur to work acceptably with a triple crank.

But manufacturer-specified capacity figures tend to be pretty conservative. (Their "largest cog" specifications, on the other hand, are usually just about right.) Most derailleurs will take up a bit more slack—typically a tooth or two more—than the spec sheet says they will. You can often pick up another tooth or two by tightening the derailleur’s “B” adjustment screw as far as it will go, so the body of the derailleur is rotated as far back as possible.

The official capacity figure also assumes that the derailleur needs to keep the chain taut at all times, even when it’s parked on granny chainring in front and the smallest freewheel cog in back.

But because we’re experienced cyclists, you and I would never use that combination anyway, since we know that it puts the chain at an extreme angle and causes rapid drive-train wear.

Come to think of it, we would never use the granny ring with either of the two smallest freewheel cogs, given that better-aligned approximations of the same ratios are usually found on the middle chainring.

And if you’re willing to make a firm policy of staying out of the smallest cogs in combination with the small chainring, your derailleur effectively gains a few additional teeth of capacity--enough, perhaps, to allow your short-cage derailleur to work acceptably with a triple crank.

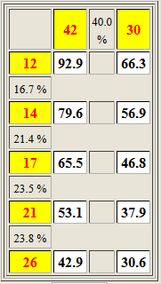

Although this setup officially requires a derailleur with a capacity of 30 teeth or more, a careful rider can pare that figure down to 26. Be sure the chain is long enough to handle the 52-32 combination! Although you won't be able to use the 32-14 or 32-16 combinations, note that the 42-18 and 42-21 combinations offer pretty much the same ratios.

Although this setup officially requires a derailleur with a capacity of 30 teeth or more, a careful rider can pare that figure down to 26. Be sure the chain is long enough to handle the 52-32 combination! Although you won't be able to use the 32-14 or 32-16 combinations, note that the 42-18 and 42-21 combinations offer pretty much the same ratios. Let's say, for example, that you have a nice old Campy-equipped Poghliaghi that's currently set up with 52-42 chainrings and a 14-16-18-21-24 freewheel. (Or call it an old Gitane if you'd rather--the numbers work out the same either way.) Let's further imagine that you have some reservations about powering over the Eroica's hills in such tall gearing.

But wait, happens if you remove the existing inner ring and bolt on a 42-tooth triplizer and a 32-tooth inner ring? Will the existing Record derailleur—which as we’ve seen has a capacity of 26 teeth—play nicely with the resulting 52-42-32 triple?

I’ll cut to the chase here: It will, but with little or nothing to spare, and only if you make sure to stay out of the 32-14 and 32-16 combinations.

The math looks like this: Subtract 32 from 52 to get 20, which is the total tooth spread of the chainrings. Now subtract 18 from 24 to get 6, representing the tooth spread of the freewheel cogs you’re actually going to use with the granny ring. (The 14- and 16-tooth cogs, remember, are off-limits.)

Add 6 and 20 and you get a capacity figure of—who knew this would work out so neatly?—26 teeth, which is the maximum that the Record derailler can accommodate. Note that we're right up against the limit here; going to a 30-tooth inner ring instead of a 32 would let the chain go slack in the 30-18 combination.

If you know the maximum capacity of the derailleur you'll be using, you can use the same simple math to figure out whether it makes sense for the gearing you have in mind, and whether you'll have to forego a cog or two at the low end to make it work.

Don’t Forget the Big-Big

But there’s one important—nay, crucial—rule to keep in mind when making any drive-train changes: THE CHAIN MUST ALWAYS BE LONG ENOUGH TO ALLOW IT TO SHIFT ONTO THE LARGEST CHAINRING AND LARGEST FREEWHEEL COG.

Like the small-small combination, of course, this is a set of ratios you wouldn’t ordinarily use. But Murphy’s law—which states that whatever can go wrong will go wrong—is ignored at one’s own peril. Everyone who spends enough time on a bike will eventually shift into the big-big combo by mistake, no matter how much they plan not to.

And if the chain isn’t long enough to let that shift happen cleanly, one of several things--all of them bad--can happen very suddenly. The chain may snap, and if you’re pounding hard uphill at the time it may pitch you over the handlebars when it does. The too-tight chain may shear the teeth off the big chainring, or blow up the rear derailleur.

An accidental shift onto the small-small combination, by contrast (and this is why cheating on derailleur capacity in the direction of too long a chain is acceptable if you're careful about it) provides no excitement whatsoever. In most cases, you’ll be alerted to the mis-shift only by the faint sound of slack chain rubbing over the drive-side chainstay. Shift up to the next biggest cog in back and the problem goes away, with no harm done except for some imperceptible wear to the paint.

You Can, But Do You Really Want To?

So am I saying that running a triplized crank with a short-cage derailleur is a good idea?

Not really. The short-cage-with-a-triple approach has the advantage of letting you continue to use your original derailleur. And let's face it, it looks pretty cool. The Eroica is a celebration of old racing bikes, and old racing bikes are supposed to have short-cage derailleurs. Sure, maybe you do have a triple up front, but that's a lot less obvious. You can hardly see the granny chainring behind the two outer ones, can you?

But cheating on derailleur capacity does mean that you'll spend at least some time riding around with excess slack in your chain, since you're sure to unintentionally shift into one of the off-limits combinations from time to time. That carries some risk of your chain derailing, which is inconvenient at best.

And when you come right down to it, the 35.4 inch low in the 32-26 setup charted above isn't really all that low. In fact, if you're running a Stronglight 93 crankset, you can get a comparable low from a double by installing a 37-tooth small ring (see the previous post for more on this).

The bottom line is that the short-cage option probably makes the most sense for staunch Campagnolo adherents, whose 144 BCD cranksets limit them to a 42-tooth small ring in the standard double configuration.

But if you can live with the look of a long-cage derailleur--which will let you use a granny ring of as small as 24 teeth--you can provide your old racing machine with the same low gearing you'd find on a modern touring bike.

But wait, happens if you remove the existing inner ring and bolt on a 42-tooth triplizer and a 32-tooth inner ring? Will the existing Record derailleur—which as we’ve seen has a capacity of 26 teeth—play nicely with the resulting 52-42-32 triple?

I’ll cut to the chase here: It will, but with little or nothing to spare, and only if you make sure to stay out of the 32-14 and 32-16 combinations.

The math looks like this: Subtract 32 from 52 to get 20, which is the total tooth spread of the chainrings. Now subtract 18 from 24 to get 6, representing the tooth spread of the freewheel cogs you’re actually going to use with the granny ring. (The 14- and 16-tooth cogs, remember, are off-limits.)

Add 6 and 20 and you get a capacity figure of—who knew this would work out so neatly?—26 teeth, which is the maximum that the Record derailler can accommodate. Note that we're right up against the limit here; going to a 30-tooth inner ring instead of a 32 would let the chain go slack in the 30-18 combination.

If you know the maximum capacity of the derailleur you'll be using, you can use the same simple math to figure out whether it makes sense for the gearing you have in mind, and whether you'll have to forego a cog or two at the low end to make it work.

Don’t Forget the Big-Big

But there’s one important—nay, crucial—rule to keep in mind when making any drive-train changes: THE CHAIN MUST ALWAYS BE LONG ENOUGH TO ALLOW IT TO SHIFT ONTO THE LARGEST CHAINRING AND LARGEST FREEWHEEL COG.

Like the small-small combination, of course, this is a set of ratios you wouldn’t ordinarily use. But Murphy’s law—which states that whatever can go wrong will go wrong—is ignored at one’s own peril. Everyone who spends enough time on a bike will eventually shift into the big-big combo by mistake, no matter how much they plan not to.

And if the chain isn’t long enough to let that shift happen cleanly, one of several things--all of them bad--can happen very suddenly. The chain may snap, and if you’re pounding hard uphill at the time it may pitch you over the handlebars when it does. The too-tight chain may shear the teeth off the big chainring, or blow up the rear derailleur.

An accidental shift onto the small-small combination, by contrast (and this is why cheating on derailleur capacity in the direction of too long a chain is acceptable if you're careful about it) provides no excitement whatsoever. In most cases, you’ll be alerted to the mis-shift only by the faint sound of slack chain rubbing over the drive-side chainstay. Shift up to the next biggest cog in back and the problem goes away, with no harm done except for some imperceptible wear to the paint.

You Can, But Do You Really Want To?

So am I saying that running a triplized crank with a short-cage derailleur is a good idea?

Not really. The short-cage-with-a-triple approach has the advantage of letting you continue to use your original derailleur. And let's face it, it looks pretty cool. The Eroica is a celebration of old racing bikes, and old racing bikes are supposed to have short-cage derailleurs. Sure, maybe you do have a triple up front, but that's a lot less obvious. You can hardly see the granny chainring behind the two outer ones, can you?

But cheating on derailleur capacity does mean that you'll spend at least some time riding around with excess slack in your chain, since you're sure to unintentionally shift into one of the off-limits combinations from time to time. That carries some risk of your chain derailing, which is inconvenient at best.

And when you come right down to it, the 35.4 inch low in the 32-26 setup charted above isn't really all that low. In fact, if you're running a Stronglight 93 crankset, you can get a comparable low from a double by installing a 37-tooth small ring (see the previous post for more on this).

The bottom line is that the short-cage option probably makes the most sense for staunch Campagnolo adherents, whose 144 BCD cranksets limit them to a 42-tooth small ring in the standard double configuration.

But if you can live with the look of a long-cage derailleur--which will let you use a granny ring of as small as 24 teeth--you can provide your old racing machine with the same low gearing you'd find on a modern touring bike.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed